| |

There was a Rhino named Davey

Whose tail was short and wavy

He liked to cook

As he read a book

But sometimes he splashed it with gravy.

|

|

Louis Slobodkin wrote that limerick for a pamphlet published in the 1970s, illustrated by Edward Gorey, called "Limericks for Book Week." Book Week was begun in 1912 by the American Booksellers Association and three years later the Chief Librarian of the Boy Scouts of America

proposed the creation of Children's Book Week, which is still celebrated every year the week before Thanksgiving. Slobodkin had always been a great fan of books and libraries, if not the rigors of public school itself. As the extraterrestrial Marty says in Round Trip Space Ship, in which Eddie is forever visiting his grandmother's farm "up above Albany" whenever he is visited from up above by the "little man from Martinea": "All Martineans read before walk or talk."

proposed the creation of Children's Book Week, which is still celebrated every year the week before Thanksgiving. Slobodkin had always been a great fan of books and libraries, if not the rigors of public school itself. As the extraterrestrial Marty says in Round Trip Space Ship, in which Eddie is forever visiting his grandmother's farm "up above Albany" whenever he is visited from up above by the "little man from Martinea": "All Martineans read before walk or talk."

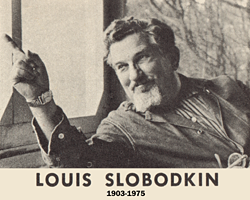

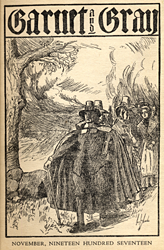

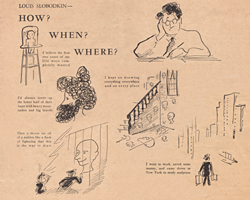

Louis Slobodkin (who also liked to cook and read) got a taste of the critics at an early age. He recalls an English teacher from his Albany High School days named Elly Mae Pluck, "(who sort of looked like that)," he wrote, "sort of a bloomer-girl type, scornfully asking me ... apropos of nothing, while I was mispronouncing a passage from As You Like It in oral exercise—Slobodkin, so you're going to be an artist? ... There was no use reminding that woman of little faith that I was then, at fourteen, the chief cartoonist of the Garnet and Gray,

Louis Slobodkin (who also liked to cook and read) got a taste of the critics at an early age. He recalls an English teacher from his Albany High School days named Elly Mae Pluck, "(who sort of looked like that)," he wrote, "sort of a bloomer-girl type, scornfully asking me ... apropos of nothing, while I was mispronouncing a passage from As You Like It in oral exercise—Slobodkin, so you're going to be an artist? ... There was no use reminding that woman of little faith that I was then, at fourteen, the chief cartoonist of the Garnet and Gray,

our high-school newspaper. She must have known that and disapproved heartily. Maybe she felt all members of the G. and G. staff should have a passing scholastic record like the football squad before they were allowed to play with the arts. For her information, if she's still around ... and for all others who sneer at inarticulate, mispronouncing, infinitive-splitting plastic artists—it is the boast of some of the best sculptors and painters I've ever known that they're completely illiterate and, for some reason, proud of it ... Her question had come out of the blue. I was having enough trouble with Shakespeare's vagaries without her heckling, and all I could answer was yeh!"

our high-school newspaper. She must have known that and disapproved heartily. Maybe she felt all members of the G. and G. staff should have a passing scholastic record like the football squad before they were allowed to play with the arts. For her information, if she's still around ... and for all others who sneer at inarticulate, mispronouncing, infinitive-splitting plastic artists—it is the boast of some of the best sculptors and painters I've ever known that they're completely illiterate and, for some reason, proud of it ... Her question had come out of the blue. I was having enough trouble with Shakespeare's vagaries without her heckling, and all I could answer was yeh!"

So, Slobodkin did go on to be an artist. But before I tell you more about how he found his calling with art, I'd like to tell you just a bit about how I found my calling with him. One day, several years ago, I was asked by a colleague at the [New York] State Museum if I would be willing to read a book aloud to the after-school club kids and I said that I would. I decided to read them

The Hundred Dresses by Eleanor Estes. I had loved that book as a kid myself and had recently picked up a paperback copy of it. This would give me the chance to reconnect with an old favorite and to share the experience with others. The pictures in particular brought back fond memories and I noted for the first time, with mild curiosity, the illustrator's name: Louis Slobodkin.

The Hundred Dresses by Eleanor Estes. I had loved that book as a kid myself and had recently picked up a paperback copy of it. This would give me the chance to reconnect with an old favorite and to share the experience with others. The pictures in particular brought back fond memories and I noted for the first time, with mild curiosity, the illustrator's name: Louis Slobodkin.

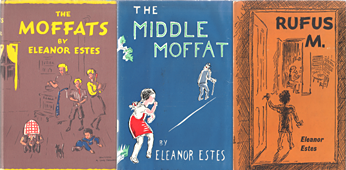

A short time after that, I came across a book called Mr. Spindles and the Spiders in a used bookstore and was pleasantly surprised to find that it too was illustrated by this selfsame Slobodkin. At some point it also dawned on me that he had done the drawings for Eleanor Estes' famous Moffat books as well.

After mulling all of this over, I suddenly declared to myself while walking to work one day: "Louis Slobodkin is my favorite children's book illustrator!" And perhaps that would have been that, had I not been idly browsing the American Library Association's "Best Sites for Kids" website while staffing the reference desk later on that afternoon. Enter the last name of your favorite author or illustrator, it prompted me, so I duly typed in: SLOBODKIN. "Louis Slobodkin was born on February 19th ..." it began. I stared in amazement. February 19th is my birthday too! And I love a good coincidence. It was just what I'd always wanted—a kidlit kindred spirit.

After mulling all of this over, I suddenly declared to myself while walking to work one day: "Louis Slobodkin is my favorite children's book illustrator!" And perhaps that would have been that, had I not been idly browsing the American Library Association's "Best Sites for Kids" website while staffing the reference desk later on that afternoon. Enter the last name of your favorite author or illustrator, it prompted me, so I duly typed in: SLOBODKIN. "Louis Slobodkin was born on February 19th ..." it began. I stared in amazement. February 19th is my birthday too! And I love a good coincidence. It was just what I'd always wanted—a kidlit kindred spirit.

This was also right around the time I had my eBay epiphany. The site is a veritable fount of affordable old books, many of them library discards. I began randomly amassing piles of out-of-print Slobodkin titles, until one day I received in the mail a book that still had its dust jacket on it and proceeded to read on the back flap: "Louis Slobodkin was born in Albany, New York." Well, that was it. I immediately embarked upon a full-scale quest to learn everything I could about this man's many books, which number nearly ninety, along with his sculptures, which are displayed in dozens of museums, public buildings, and private collections worldwide. Not too bad for a dyslexic dropout from the Miss Pluck School of Public Correction.

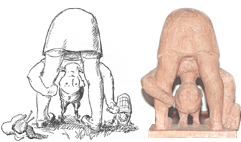

Louis was always eager to get on with the business of drawing pictures. "I believe," he writes in the May 1947 issue of Child Life magazine, "that the first two years of my life were completely wasted." He says he always wanted to be an artist, but when his little brother gave him a lump of red modeling clay, out of which he formed an Indian who quickly became Ben Franklin—glasses were easier to make than the naked eye—he discovered the joy of sculpting. He also recalls with gratitude his first drawing lesson when he caught sight one day of an older boy drawing a face on the schoolyard fence. "It struck me all of a sudden like a flash of lightning," he says, "that this is the way to draw. We should try to draw people so they look as they do look—not flat and thin, but round and thick and deep...."

Louis was always eager to get on with the business of drawing pictures. "I believe," he writes in the May 1947 issue of Child Life magazine, "that the first two years of my life were completely wasted." He says he always wanted to be an artist, but when his little brother gave him a lump of red modeling clay, out of which he formed an Indian who quickly became Ben Franklin—glasses were easier to make than the naked eye—he discovered the joy of sculpting. He also recalls with gratitude his first drawing lesson when he caught sight one day of an older boy drawing a face on the schoolyard fence. "It struck me all of a sudden like a flash of lightning," he says, "that this is the way to draw. We should try to draw people so they look as they do look—not flat and thin, but round and thick and deep...."

"At the age of fifteen during my third year at high school," he says, "I decided to quit school and study art. I forced my parents' permission by instigating the first one-man sit-down strike I'd ever heard of. I would attend class at the high school, but I would refuse to do any work. After enough zeroes piled up I was allowed to leave school. I worked that spring and summer, bell-hopping in a hotel and earned enough money to take me to New York the following October." Louis tells of having seen the larger-than-life "Diamond" Jim Brady and Lillian Russell at the Ten Eyck Hotel in downtown Albany while working there. That historic building must have been an inspiring place for an aspiring architectural sculptor to be ensconced, and Louis' thoughts while running the lift were often of an elevated kind. He passed the time between passengers reading the classics, he says, and looked forward to the occasions when he would get stuck between floors.

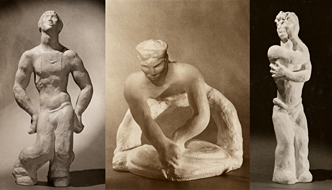

The following fall, the Slobodkin family moved to Brooklyn and Louis began his studies at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design. The Institute had only been established for two years before the young would-be sculptor arrived on its doorstep in 1918. The school, whose student body largely comprised immigrants and first-generation Americans, provided training for union jobs in the architectural and building trades as opposed to the fine arts. Louis excelled there, while holding down numerous part-time jobs, earning 22 medals in life study, drawing, and sculpture. He was also the recipient of a Louis Tiffany Foundation fellowship, which landed him an internship at Tiffany's Art Nouveau estate in Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island.

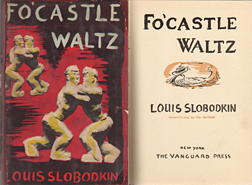

After a dispiriting stint in a commercial modeling studio that did not support the ideals he had acquired at the academy, the 21-year-old got a wild hair to sign on as a deckhand aboard an Argentine freighter. Two decades later, he recounts the tale of this brackish baptism in a memoir called Fo'castle Waltz. The story begins like this:

"Now, why should a fat, soft guy with glasses be waiting for (believe it or not) a Brooklyn streetcar at six o'clock on a brilliant, hot July morning? ... The rescued kitten scampered in the other direction with her honor intact for one more day, or until I'd boarded that trolley which lurched off down the street, looking for the S.S. Hermanita and the other end of the world." (Read entire excerpt from Fo'castle Waltz) Just as he had, a few years earlier, staged a "one-man sit-down strike" in high school, Louis soon finds himself committing a one-man mutiny on the high seas. You'll have to read the book yourself to learn the hows and whys of his unilateral uprising, but he concludes his saga by saying: "I never did get over my side of the story, and I can't tell, after all these years, to what degree my social and professional position has been impaired by misrepresentation. So, to clear my position, and because a sweet dame with a nice round neck (who went off and married a guy who collects bugs in the New Hebrides) said over her teacup somebody ought to put me in a book sometime, and nobody did after all these years—and because of a virgin cat—this book has been written."

After a dispiriting stint in a commercial modeling studio that did not support the ideals he had acquired at the academy, the 21-year-old got a wild hair to sign on as a deckhand aboard an Argentine freighter. Two decades later, he recounts the tale of this brackish baptism in a memoir called Fo'castle Waltz. The story begins like this:

"Now, why should a fat, soft guy with glasses be waiting for (believe it or not) a Brooklyn streetcar at six o'clock on a brilliant, hot July morning? ... The rescued kitten scampered in the other direction with her honor intact for one more day, or until I'd boarded that trolley which lurched off down the street, looking for the S.S. Hermanita and the other end of the world." (Read entire excerpt from Fo'castle Waltz) Just as he had, a few years earlier, staged a "one-man sit-down strike" in high school, Louis soon finds himself committing a one-man mutiny on the high seas. You'll have to read the book yourself to learn the hows and whys of his unilateral uprising, but he concludes his saga by saying: "I never did get over my side of the story, and I can't tell, after all these years, to what degree my social and professional position has been impaired by misrepresentation. So, to clear my position, and because a sweet dame with a nice round neck (who went off and married a guy who collects bugs in the New Hebrides) said over her teacup somebody ought to put me in a book sometime, and nobody did after all these years—and because of a virgin cat—this book has been written."

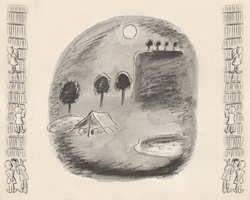

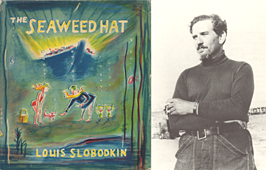

Louis was a typical Pisces who seemed drawn to watery themes, as well as to that certain uncertainty and wishy-washiness that marks the Fish. In a copy I'm lucky to own of The Seaweed Hat, published two years after Fo'castle Waltz, he writes to "Anne" (his editor, perhaps?): "Dear Anne, I'm not apologizing for this book but if I had it to do over again ... I'd ... well done is done." Perhaps it's the water sign in me as well, but Slobodkin appears especially inspired when dealing with aquatic imagery—as in Jonathan and the Rainbow in 1948 and The Little Mermaid Who Could Not Sing in 1956.

Louis was a typical Pisces who seemed drawn to watery themes, as well as to that certain uncertainty and wishy-washiness that marks the Fish. In a copy I'm lucky to own of The Seaweed Hat, published two years after Fo'castle Waltz, he writes to "Anne" (his editor, perhaps?): "Dear Anne, I'm not apologizing for this book but if I had it to do over again ... I'd ... well done is done." Perhaps it's the water sign in me as well, but Slobodkin appears especially inspired when dealing with aquatic imagery—as in Jonathan and the Rainbow in 1948 and The Little Mermaid Who Could Not Sing in 1956.

Upon resuming life as a landlubber back in the Roaring Twenties, Slobodkin created a series of sculptures based on the drawings he had done of his motley crewmates, with titles like "Sailor's Hula," "Coiling Rope," "Sailor Washing," "Sailor's Music," and "Sea Lawyer." He began work again in a studio in which his boss believed sculptors, like priests, should not be married. Louis met "Brooklyn girl Florence Gersh,"

a writer and employee in the NYC school district, and kept their wedded union under wraps until their firstborn son Larry came along in 1928, at which point he was summarily fired, Scrooge-like, just before Christmas. Slobodkin left for Paris, where he continued his studies, then returned to New York City to open his own studio. He was very active in the sculpture scene during the 1930s and early 40s. He became an instructor at the Art Students League, headed the sculpture department of the Master Institute of Roerich Museum (where he taught the blind sculptor Mark Shoesmith), served on the board of the Sculptors Guild, and directed the sculpture division of the New York City Art Project.

a writer and employee in the NYC school district, and kept their wedded union under wraps until their firstborn son Larry came along in 1928, at which point he was summarily fired, Scrooge-like, just before Christmas. Slobodkin left for Paris, where he continued his studies, then returned to New York City to open his own studio. He was very active in the sculpture scene during the 1930s and early 40s. He became an instructor at the Art Students League, headed the sculpture department of the Master Institute of Roerich Museum (where he taught the blind sculptor Mark Shoesmith), served on the board of the Sculptors Guild, and directed the sculpture division of the New York City Art Project.

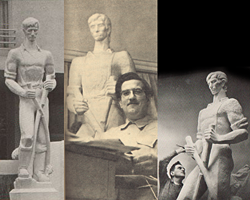

In 1939, Louis Slobodkin won a government-sponsored competition on the theme of "Unity" or "Peace," with a motif taken from history or contemporary life. This earned him the implicit right to exhibit a commissioned work at the New York World's Fair. The resultant sculpture was a 15-foot steel and plaster rendering of the young Abraham Lincoln called the Rail Joiner. But when the Slobodkins arrived at the Fair on opening day to inspect the installation, they were informed by a doorman: "'Taint here any more." The shocking word quickly went round that workmen had demolished the statue on order of Theodore Hayes, Executive Assistant to the Federal Commissioner for the World's Fair, Edward Flynn. Five days later, Slobodkin told The New York Times that, according to a source in Washington, his sculpture had indeed been set upon with sledgehammers, reportedly because a lady who "lunched with Flynn" had not found it to be in "good taste." Flynn for some reason valued this doubtful opinion over his very own as a member of the panel that had selected the Lincoln for exhibition. Despite the fact that Flynn was a strong supporter of FDR and a "dear friend" to Eleanor, the First Lady expressed admiration for the Rail Joiner and dismay over its fate in her newspaper column "My Day."

In 1939, Louis Slobodkin won a government-sponsored competition on the theme of "Unity" or "Peace," with a motif taken from history or contemporary life. This earned him the implicit right to exhibit a commissioned work at the New York World's Fair. The resultant sculpture was a 15-foot steel and plaster rendering of the young Abraham Lincoln called the Rail Joiner. But when the Slobodkins arrived at the Fair on opening day to inspect the installation, they were informed by a doorman: "'Taint here any more." The shocking word quickly went round that workmen had demolished the statue on order of Theodore Hayes, Executive Assistant to the Federal Commissioner for the World's Fair, Edward Flynn. Five days later, Slobodkin told The New York Times that, according to a source in Washington, his sculpture had indeed been set upon with sledgehammers, reportedly because a lady who "lunched with Flynn" had not found it to be in "good taste." Flynn for some reason valued this doubtful opinion over his very own as a member of the panel that had selected the Lincoln for exhibition. Despite the fact that Flynn was a strong supporter of FDR and a "dear friend" to Eleanor, the First Lady expressed admiration for the Rail Joiner and dismay over its fate in her newspaper column "My Day."

When confronted about this disturbing turn of events, Flynn's flack at first dissembled and absurdly asserted that the artwork had been placed in storage, then tried to buy the sculptor off, and finally settled on the statue being "too tall,"

adding that preview visitors had "scoffed at it." Hayes hastened to explain: "We couldn't take that sort of criticism from people representing John Q. Public. I don't care what those artist fellows think, it should never have been placed there at all." He refused to reveal its whereabouts or condition. Fellow artists rallied in protest and a public poll showed near unanimous support for the Rail Joiner. Hayes issued the following terse statement: "After all it is government property. Beyond that there is no comment." Slobodkin sought redress unsuccessfully in court, pointing out that the primary incentive for creating such a piece is the expected enhancement of one's reputation by virtue of its public display, and wishing only to know what had become of it. "A day's destruction for a year's work ... Oh, well," he said. Later, a sort of settlement was reached when a seven-foot bronze casting, now called the Fence Builder, was permanently placed at the Dept. of the Interior in Washington, D.C.

adding that preview visitors had "scoffed at it." Hayes hastened to explain: "We couldn't take that sort of criticism from people representing John Q. Public. I don't care what those artist fellows think, it should never have been placed there at all." He refused to reveal its whereabouts or condition. Fellow artists rallied in protest and a public poll showed near unanimous support for the Rail Joiner. Hayes issued the following terse statement: "After all it is government property. Beyond that there is no comment." Slobodkin sought redress unsuccessfully in court, pointing out that the primary incentive for creating such a piece is the expected enhancement of one's reputation by virtue of its public display, and wishing only to know what had become of it. "A day's destruction for a year's work ... Oh, well," he said. Later, a sort of settlement was reached when a seven-foot bronze casting, now called the Fence Builder, was permanently placed at the Dept. of the Interior in Washington, D.C.

The 1983 Milwaukee Art Museum catalog, Controversial Public Art: From Rodin to di Suvero, in reference to the Lincoln controversy, alludes to the corrosive and contagious effects of censorship in its observation that "meanwhile, the damaging of Slobodkin's life-size nude,

Bathsheba, at the Contemporary Arts Building seemed more than coincidental." It goes on to say:

"Slobodkin's wish to communicate to a wide audience, so frustrated by the World's Fair Commissioners, was amply fulfilled in his later career as an author/illustrator.

Bathsheba, at the Contemporary Arts Building seemed more than coincidental." It goes on to say:

"Slobodkin's wish to communicate to a wide audience, so frustrated by the World's Fair Commissioners, was amply fulfilled in his later career as an author/illustrator.

His ultimate perspective on the Rail Joiner's destruction is suggested in the following statement:

'[Eleven years ago last night] there was a big bonfire started by a tyrant who wanted to be an artist but could only become assistant paper-hanger. That fire was fed by books. Those books were burned for many reasons. One of the main reasons was that they were concerned with humanity and human relations. Of course those books weren't lost. They were printed on indestructible truths with the fireproof blood from the heart. My ambition is to do work which will have that much reason to exist.' " (The quote is from Slobodkin's Caldecott award acceptance speech on May 11, 1944, for his illustrations in James Thurber's book Many Moons.)

His ultimate perspective on the Rail Joiner's destruction is suggested in the following statement:

'[Eleven years ago last night] there was a big bonfire started by a tyrant who wanted to be an artist but could only become assistant paper-hanger. That fire was fed by books. Those books were burned for many reasons. One of the main reasons was that they were concerned with humanity and human relations. Of course those books weren't lost. They were printed on indestructible truths with the fireproof blood from the heart. My ambition is to do work which will have that much reason to exist.' " (The quote is from Slobodkin's Caldecott award acceptance speech on May 11, 1944, for his illustrations in James Thurber's book Many Moons.)

One summer around the time of the World's Fair debacle, the Slobodkins were vacationing on Cape Ann, when they met, as Louis says, "two nice young people, sunning themselves on an old stone wall." This auspicious meeting would mark the beginning of Slobodkin's career as a book illustrator. He tells the story in his Caldecott Medal address: "They were the Estes, Eleanor and Rice, and the strangest thing about them was—they were librarians. Now I don't know why that should have seemed strange, but I have had the same reaction when I met my first anthropologists and again when I met my first professional wrestlers. Come to think of it, maybe sculptors seem strange to people, too, these fellows who stand hacking away at stone or building a lump of clay for a long, long time. Anyway, I met the Estes, and since then I've met so many librarians and they're all such nice people."

Estes, who was plotting a career move herself, persuaded Louis to exchange chisel for pencil and collaborate with her on a children's book called The Moffats.

This was a great success and he followed up with two more Moffat books over the next two years (his wife would hush the children during this period by telling them, "Papa's making moffats"), along with Estes' next one, The Sun and the Wind and Mr. Todd.

This was a great success and he followed up with two more Moffat books over the next two years (his wife would hush the children during this period by telling them, "Papa's making moffats"), along with Estes' next one, The Sun and the Wind and Mr. Todd.

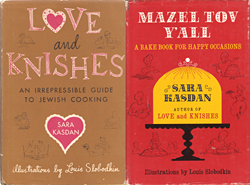

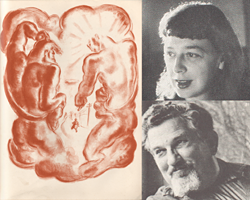

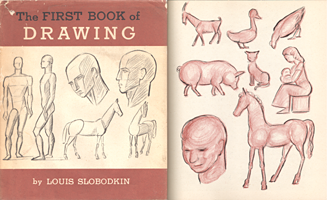

Slobodkin then tried his own hand at writing, with three books dedicated to his two children, Larry and Michael. In 1958, he came full circle with The First Book of Drawing, which opens—as if speaking to his own inner child—with the assurance that "the ancient Greeks (some of whom you know were great artists) used the same word for 'drawing' as they did for 'writing.' It made good sense, really." That word is graphos. Slobodkin wrote and drew almost fifty children's books all told, and illustrated nearly forty more, including three by young adult biographer Nina Brown Baker, and, alas, just one by the great Edward Eager, Red Head.

Slobodkin then tried his own hand at writing, with three books dedicated to his two children, Larry and Michael. In 1958, he came full circle with The First Book of Drawing, which opens—as if speaking to his own inner child—with the assurance that "the ancient Greeks (some of whom you know were great artists) used the same word for 'drawing' as they did for 'writing.' It made good sense, really." That word is graphos. Slobodkin wrote and drew almost fifty children's books all told, and illustrated nearly forty more, including three by young adult biographer Nina Brown Baker, and, alas, just one by the great Edward Eager, Red Head.

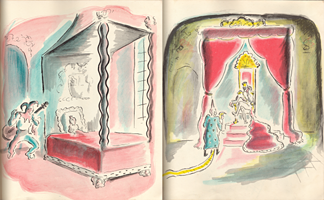

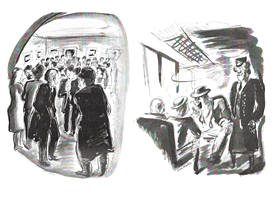

Louis also dabbled in grown-up graphic art and New Yorker-ish cartoons, but seemed to prefer the free reign to his imagination that children's books afforded him. In Hustle and Bustle,

Louis also dabbled in grown-up graphic art and New Yorker-ish cartoons, but seemed to prefer the free reign to his imagination that children's books afforded him. In Hustle and Bustle,

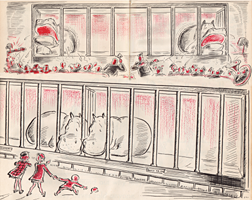

the two phlegmatic friends express their fellow feeling through baggy body language and lachrymose floods. The reader can't know what caused the great rift in these hippos' relationship, but as one observes the glacial shifting of positions in their adjoining cages at the zoo, it becomes clear that it's not the making of the fight, but the making up, that matters. Slobodkin stresses on nearly every page the intimate connection between happiness and friendliness, often with subtle humor. A tiny road sign reading City Limits: Stop and Say Goodbye;

the two phlegmatic friends express their fellow feeling through baggy body language and lachrymose floods. The reader can't know what caused the great rift in these hippos' relationship, but as one observes the glacial shifting of positions in their adjoining cages at the zoo, it becomes clear that it's not the making of the fight, but the making up, that matters. Slobodkin stresses on nearly every page the intimate connection between happiness and friendliness, often with subtle humor. A tiny road sign reading City Limits: Stop and Say Goodbye;

the Police Band playing a "sad song called Never forget the forget-me-nots!"; the Mayor giving a speech that begins, "Please be friends because ..." all conspire to encourage the feuding duo to patch things up. Which, after a good cathartic and civic-minded cry, they do. "Perhaps this sometimes happens to all Good Friends," opines the author, "and they don't know why. But Hustle and Bustle were never unfriendly again." Slobodkin is not above inserting little in-joking autobiographical grace notes into his work: Hustle's cage displays a sign reading "Jan 1905" and Bustle's says "Feb 1903," which are the birthdates of Florence and Louis Slobodkin. This charming book was an homage to their marriage.

the Police Band playing a "sad song called Never forget the forget-me-nots!"; the Mayor giving a speech that begins, "Please be friends because ..." all conspire to encourage the feuding duo to patch things up. Which, after a good cathartic and civic-minded cry, they do. "Perhaps this sometimes happens to all Good Friends," opines the author, "and they don't know why. But Hustle and Bustle were never unfriendly again." Slobodkin is not above inserting little in-joking autobiographical grace notes into his work: Hustle's cage displays a sign reading "Jan 1905" and Bustle's says "Feb 1903," which are the birthdates of Florence and Louis Slobodkin. This charming book was an homage to their marriage.

Despite once writing, "I'm a homebody and I've always felt Diogenes could get all the excitement anybody needed just sitting in his barrel—as long as there were no restraints put on his flights of fancy," Louis enjoyed the broadening effects of travel and spent time in Europe—for study, work, and pleasure—on at least half a dozen occasions, including an extended stay at an Italian artists' colony in Taormino.

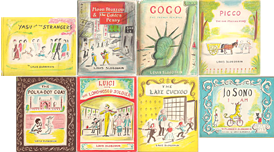

In the early 1960s, the Slobodkins took a trip around the world, traveling to France, Switzerland, China, Japan, India, and Italy. After returning to the States, Louis produced a number of children's books set in the various countries they had visited: Gogo the French Sea Gull, The Late Cuckoo, Moon Blossom and the Golden Penny, Yasu and the Strangers, The Polka-Dot Goat, Luigi and the Long-Nosed Soldier, and Picco the Sad Italian Pony. He also illustrated the Italian primer written by Florence, Io Sono, I Am: Italian with Fun.

In the early 1960s, the Slobodkins took a trip around the world, traveling to France, Switzerland, China, Japan, India, and Italy. After returning to the States, Louis produced a number of children's books set in the various countries they had visited: Gogo the French Sea Gull, The Late Cuckoo, Moon Blossom and the Golden Penny, Yasu and the Strangers, The Polka-Dot Goat, Luigi and the Long-Nosed Soldier, and Picco the Sad Italian Pony. He also illustrated the Italian primer written by Florence, Io Sono, I Am: Italian with Fun.

Slobodkin's sculptures have been exhibited at the Whitney Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the National Academy of Design, the Corcoran Gallery, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Garfield Park Art Gallery, and the Riverside Museum.

His first public commission was for the "Tropical Postman" at the Madison Square Post Office in New York. He gave lectures at the Metropolitan Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and, if I'm not mistaken, this very one we're sitting in right now. Slobodkin served on the faculty of numerous art schools in New York City and is the author of the textbook Sculpture: Principles and Practice. Indeed, his first crack at book illustration betrays a sculptor's practiced eye. The Moffats, as an admiring critic once pointed out, evince the sturdy style of a sculptural armature. Some of you may remember reading the Moffat books as children, and a few of you may even recall Clif Bradt of the Knickerbocker News, who once wrote: "The Moffats is a kids' book, but the kids range from 10 to 110."

His first public commission was for the "Tropical Postman" at the Madison Square Post Office in New York. He gave lectures at the Metropolitan Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and, if I'm not mistaken, this very one we're sitting in right now. Slobodkin served on the faculty of numerous art schools in New York City and is the author of the textbook Sculpture: Principles and Practice. Indeed, his first crack at book illustration betrays a sculptor's practiced eye. The Moffats, as an admiring critic once pointed out, evince the sturdy style of a sculptural armature. Some of you may remember reading the Moffat books as children, and a few of you may even recall Clif Bradt of the Knickerbocker News, who once wrote: "The Moffats is a kids' book, but the kids range from 10 to 110."

I'm certain this accolade was intended for Louis Slobodkin as much as it was for Eleanor Estes.

I'm certain this accolade was intended for Louis Slobodkin as much as it was for Eleanor Estes.

His disarming drawings have been praised again and again ("You like to keep on looking," murmured May Lamberton Becker in the New York Herald Tribune). And it seems the man himself could draw a good bit of awe as well. On the dust jacket to Fo'castle Waltz, his publisher at Vanguard Press wrote: "We have boisterous evidence that he has two strapping sons, who, when you ask for him on the telephone, demand: 'Do you mean Mr. Slobodkin, the sculptor, painter, author, lecturer, book designer, illustrator, chef, factory hand, chicken farmer, bell-hop, dish-washer?' We settle all that by merely asking for the Eminent."

So here's to Albany's own, the Eminent Louis Slobodkin!