I was born in Albany, New York, February 19, 1903. When I discovered I could draw I decided to become an artist. Someone gave me a few pounds of modeling clay when I was thirteen so I became a sculptor. I read every available book on sculpture and sculptors in the Albany libraries, also studied all the photographic reproductions I could get, mainly very washy prints of Hellenic Greek, some Italian Renaissance and sweet seventeenth-century French sculptures. At the age of fifteen during my third year at high school I decided to quit school and study art. I forced my parents’ permission by instigating the first one-man sitdown strike I’d ever heard of. I would attend class at the high school, but would refuse to do any work. After enough zeroes piled up I was allowed to leave school. I worked that spring and summer, bell-hopping in a hotel and earned enough money to take me to New York the following October.

I registered at the Beaux-Arts and studied in the life modeling and drawing classes for the next five years, taking time out during the spring and summer to earn money as a factory hand, waiter, dishwasher or the like, to keep me going.

I registered at the Beaux-Arts and studied in the life modeling and drawing classes for the next five years, taking time out during the spring and summer to earn money as a factory hand, waiter, dishwasher or the like, to keep me going.

The instruction at the Beaux-Arts was voluntary and instructors were changed every three months. There were then three life modeling classes and different instructors in each class (the drawing class had no instructor). When conditions were right I attended classes some nine to twelve hours a day. To give a list of the instructors would demand that I name almost every mature sculptor in New York. The school was near the Metropolitan Museum and I’d manage to get a few hours every other day there to study the sculpture of the early Greeks, Egyptians, Assyrians, Chinese and other ancient peoples.

About this time my ideas on sculpture began to clarify themselves. I felt then as I do now that primarily sculpture is made to become part of the earth or to be collaborated with some building which is firmly anchored. I objected to “floating sculpture.” It seemed to me rather silly to carve a huge stone and ship it from exhibit to exhibit in some vague hope that something would happen. Through the ages until quite recently sculptors did their work for some definite spot on this earth and it was left there.

About this time my ideas on sculpture began to clarify themselves. I felt then as I do now that primarily sculpture is made to become part of the earth or to be collaborated with some building which is firmly anchored. I objected to “floating sculpture.” It seemed to me rather silly to carve a huge stone and ship it from exhibit to exhibit in some vague hope that something would happen. Through the ages until quite recently sculptors did their work for some definite spot on this earth and it was left there.

I prepared myself for architectural sculpture in hopes that I might work in the grand tradition. First I got a job as an apprentice in what the art students called a “cabbage modeling” shop—that is, a commercial architectural modeling studio which in those days turned out cheap imitations of all the accepted styles of acanthus leaf decorations, the garlands and so forth—Louis XIV, Louis XV, Louis XVI, (ad infinitum), Roman, Romanesque, early Renaissance, later Renaissance, or what have you. After six months of mixing clay, cutting glue, carrying plaster, I felt I was not attaining my artistic ideal. So I quit. I worked my passage down to Argentina as a deck hand in 1923, and then came back to try again.

I prepared myself for architectural sculpture in hopes that I might work in the grand tradition. First I got a job as an apprentice in what the art students called a “cabbage modeling” shop—that is, a commercial architectural modeling studio which in those days turned out cheap imitations of all the accepted styles of acanthus leaf decorations, the garlands and so forth—Louis XIV, Louis XV, Louis XVI, (ad infinitum), Roman, Romanesque, early Renaissance, later Renaissance, or what have you. After six months of mixing clay, cutting glue, carrying plaster, I felt I was not attaining my artistic ideal. So I quit. I worked my passage down to Argentina as a deck hand in 1923, and then came back to try again.

I haunted the doorsteps of the men who were considered the best architectural sculptors in New York until I got a job as assistant sculptor. I would work with one of them until the commission was finished or until I was fired or quit because of some difference in philosophic attitude or artistic theory.

I learned as much as I could about blue prints, the mediums of architectural sculpture and the practical processes. I earned a pretty good living and managed to get a year and a half in Europe working as an assistant. That year and a half meant a great deal to me. I was able to study the original sculpture in its true setting in place of a lot of reproductions in casts and photographs.

I had hoped that after I’d proved my ability I’d be commissioned to do some work of my own. But unfortunately that’s not the way work was awarded. I continued to work as an assistant sculptor for a number of years after I had discovered the fallacy of my hopes, and it seemed as if I would never be able to do my own sculpture the way I wanted to do it.

My first real “break” came when I was awarded the Hawaiian Postman commission through the Section of Fine Arts competition in October, 1935. Since then I’ve been awarded a number of small jobs on the merits of sketches I submitted in other competitions. Until recently I’ve headed the sculpture department of the Master Institute of Roerich Museum.

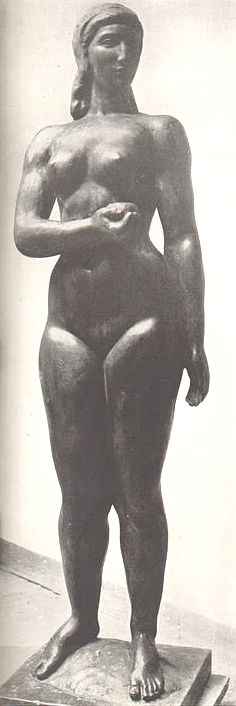

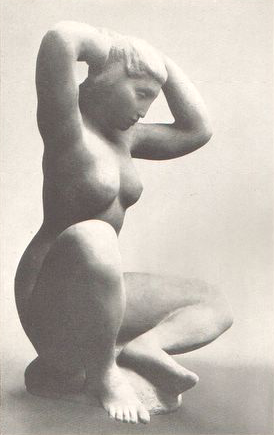

Teaching, I found, demanded that I express clearly what I felt were the essential qualities of sculpture: plastic emotion, flow, rhythm, unity, contrast and balance of geometric shape, sympathetic understanding of the materials with which sculpture is made. I believe I learned something about sculpture from teaching it.

Teaching, I found, demanded that I express clearly what I felt were the essential qualities of sculpture: plastic emotion, flow, rhythm, unity, contrast and balance of geometric shape, sympathetic understanding of the materials with which sculpture is made. I believe I learned something about sculpture from teaching it.

I can’t remember from whom I learned to hate empty surface, surface benders and those who stuff shapes that lack the flow and rhythm that living sculpture must have. Nor can I remember who taught me to appreciate and love the plastic beauty of the Egyptian, Hindu, Persian, Negro, early Greek, thirteenth-century Gothic, Mayan, Chinese and early Renaissance sculptures and their natural offspring—the works of Lehmbruck, Brancusi, Meunier, Epstein.

I’ve done some “floating sculpture” these past few years; I couldn’t sit on my hands waiting for work to come along. My “floating sculpture” not only floats—it folds up; that is, if I model something over six feet high I have it cast with a center joint so that I can take it apart and fold it away between exhibits. I won’t carve a stone which I can’t lift with only one man to help.

I’ve exhibited at the Whitney Museum, the New School of Social Research, the Architectural League, the Brooklyn Museum, the National Academy of Design, the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, the Garfield Park Art Gallery and the Art Institute of Chicago.

I’ve exhibited at the Whitney Museum, the New School of Social Research, the Architectural League, the Brooklyn Museum, the National Academy of Design, the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, the Garfield Park Art Gallery and the Art Institute of Chicago.

My interest in the arts other than sculpture is in architecture, symphonic and instrumental music (I can live without opera), ballet, folk and religious dancing of the so-called primitives (I can do without interpretive and modern dance forms), and easel and mural painting. I prefer the cinema to the legitimate theatre.

One last comment on architectural sculpture. I believe that if the architects build their buildings and leave space for the sculpture with which they intend to embellish it and permit the sculptor commissioned for the work to study his job we’ll produce a real architectural sculpture here in America. I believe that the sculptor should confer at the outset with the architect who is designing the building. I feel the system we now employ of completing our sculpture models from only blueprint specifications before the foundations are even laid is a false one.

I believe, too, that the subject matter for our sculpture can be found in the life that exists around us today. I always felt a little silly modeling flying naked Mercurys to express speed or fat ladies in cheese cloth holding cornucopias of obscure fruit to express agricultural plenty.

—Louis Slobodkin, Magazine of Art, June, 1939

|